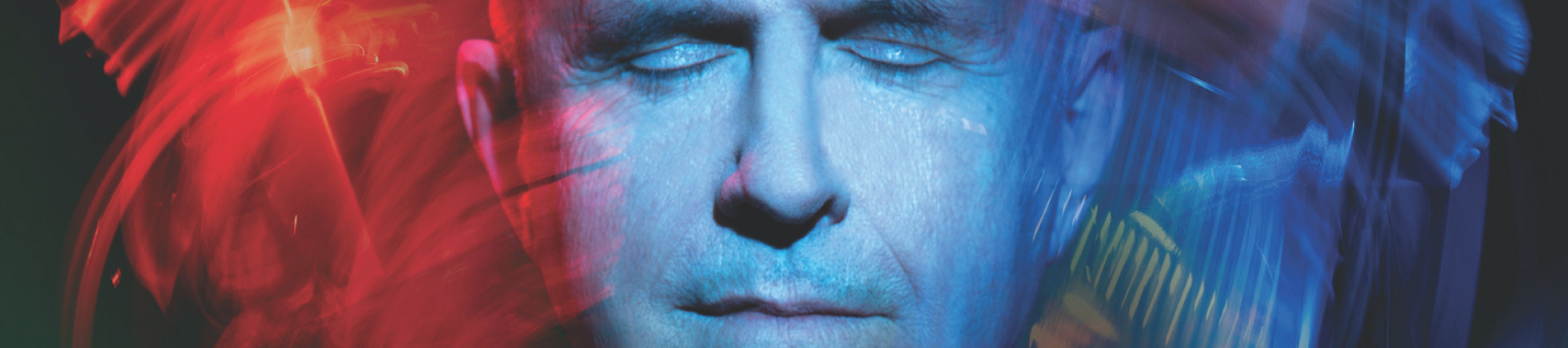

Howard Jones

Positive Thinking and Music’s Power to Transform

“I was definitely doing my own thing,” says Howard Jones when asked about the Second British Invasion, which included Duran Duran and Human League. “I wasn’t part of a scene. I was in High Wycombe,” he laughs. “There was no scene.”

The name Howard Jones holds a special place in the history of both synthesizers and pop music. His bright, optimistic hits like “No One is to Blame,” and “Things Can Only Get Better” flew in the face of the '80s overriding sense of capitalism run amuck. The latter tune appears in the current season of cultural phenomena Stranger Things, attesting to the power of Jones’ positive messages.

“It’s what I set out to do right from the beginning,” Jones explains. “I didn’t want to write doom and gloom lyrics, because there was plenty of that around. Knowing cynicism very well within myself, I wanted to do the opposite in my work.”

I didn’t want to write doom and gloom lyrics, because there was plenty of that around. Knowing cynicism very well within myself, I wanted to do the opposite in my work.

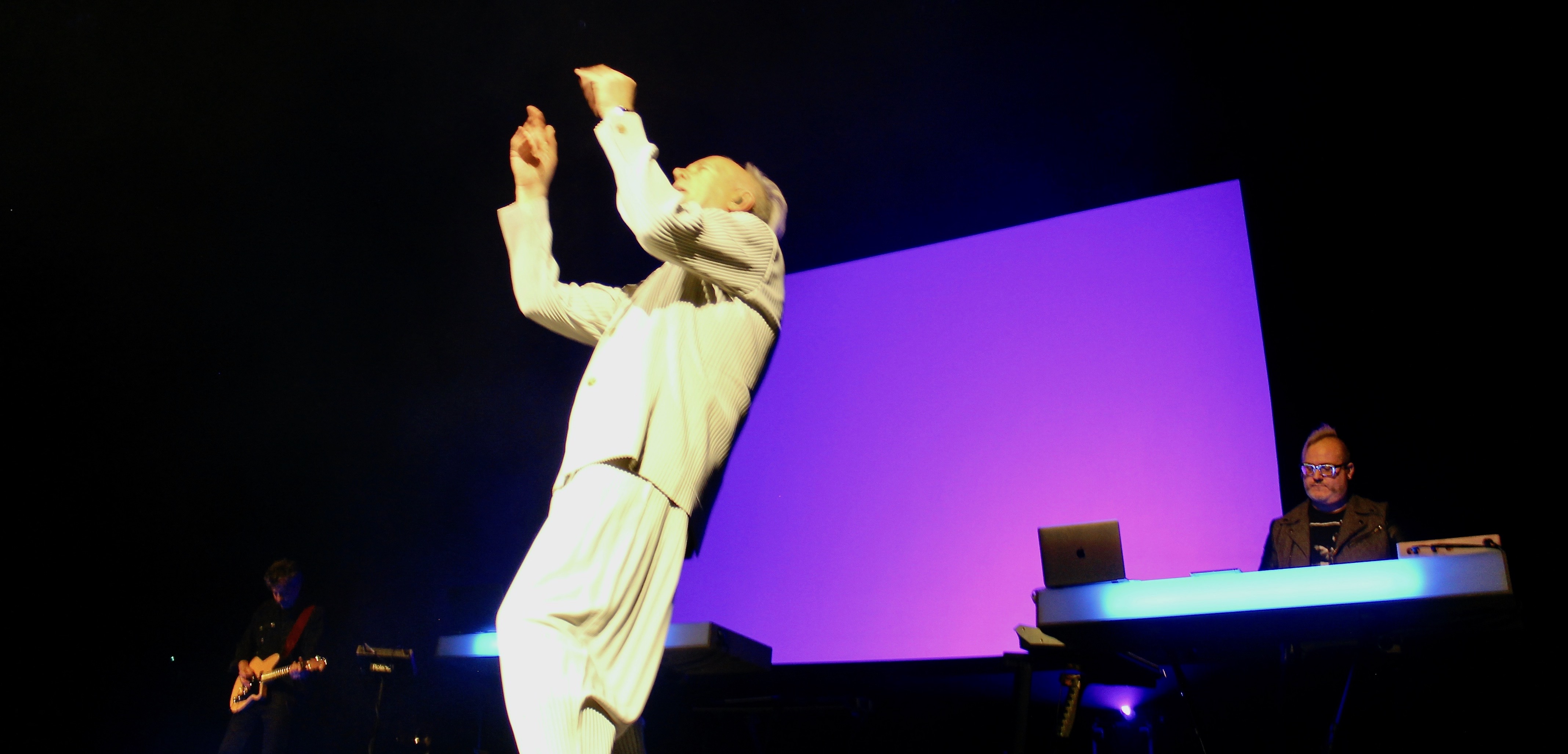

Speaking backstage at Seattle’s Moore Theater with longtime collaborator Robbie Bronnimann, Jones is friendly and generous. His hair is dyed a fashionable silver and cut in a futuristic quasi-mohawk, a style Bronnimann mirrors. Jones chooses his words carefully, each phrase evoking the same spirit as his lyrics.

The title of Jones’ latest release, Transform, is appropriate. The record takes elements of prior musical triumphs and fashions them into something undeniably contemporary. While Jones admits his following wanted another electronic record, Transform actually emerged from another project.

“I was asked to write songs for the Eddie the Eagle film,” he explains, adding, “I loved the script, ‘cus it’s set in the ‘80s.” The film inspired Jones to revisit his electro-pop beginnings, which he'd set aside for a bit in favor of more experimental sounds. "I asked myself some fundamental questions like, 'How did I make those early records?' and 'What instruments did I use?’ It was time to get back to the basics: synths and drum machines and go from there.”

Many of the synths and drum machines on those records were made by Roland. “I was really fortunate to be born in a time when those incredible instruments were available. For me, anything with keys on it, I wanted to be part of that.”

One piece of Roland gear long associated with Jones came into the singer’s life in a rather unexpected way. “Me and my wife had an accident, and the insurance money from that bought the JUPITER-8. I wouldn’t have been able to afford it otherwise.”

Bronniman and Jones have an easy rapport, one which speaks to their long working history. “My introduction to electronic music was Howard’s Human’s Lib,” confides Bronniman. “That was the first electronic album I was given. From then on, I was into all the electronic things I could get my hands on.”

“Robbie used to send me tapes,” chimes in Jones.

“When I was a teenager, I used to leave my cassettes at his front door," Bronnimann chuckles.

“We actually met by chance in Maidenhead years later, and I invited Robbie over. He set up a little studio at my place where he did all sorts of stuff. All my projects since then, Robbie’s been involved.” That partnership has evolved over the years. Though the two both live in the Southwest of England, file-sharing now plays a significant role. “We use Dropbox a lot,” Jones laughs.

“When we both started working, we both had exactly the same gear,” says Bronnimann, “so we could go, ‘Here’s a file,' load it into a session, and all the instruments came up.”

“I could not keep up with his acquisition of gear,” interjects Jones. “Every time I go to Robbie’s studio, there are about a dozen new things he’s acquired.”

“Howard’s got a set of tools he loves,” continues Bronnimann. “I have all those tools so we can start from that place. It’s never backwardly compatible,” he says, acknowledging his growing studio environment. “Once I get a hold of them, they get assimilated into a bigger ecosystem.”

Transform is a layered record, one that rewards repeated listens. This method dates back to Jones’ first hit, “New Song,” which placed organ stabs amid all the bubbly bass and synth sounds. Jones confirms this is always his intention. “We try to have layers of additional interest you’ll discover over time. I love records like that, myself.”

That same sensitivity to the integrity of Jones’ material extends to the current live rig for the Transform tour. “I run an Ableton setup with a number of controllers, and chop the songs up into verses, choruses, bridges. We have a number of stems we can vary—bring things in and out, change things on the fly. The visuals follow the arrangements, so when we switch the songs up the images jump around too. Everything clocks without being static.”

Howard adds, “If I want to do x-number of choruses or extend solos we can do that. We wanted to make it a bit edgy and allow for accidental things to happen. The way a rock band would say, ‘Let’s do another chorus.’ We want that with electronic music as well.”

The current touring setup also relies heavily on Roland instruments and other tools, Bronnimann reveals. “We’ve got two SYSTEM-8s. We’ve got the whole Roland V-Mixing System as the backbone of our touring rig and the RD-2000 piano is right up front.”

Similarly, Jones effuses about Roland Cloud and its recreations of classic synths like the JX-3P. “I love the sound of it. It’s fat and big and chunky.”

“We used Roland Cloud all over the album,” Bronnimann adds. “It’s a great resource.”

Still, Jones has some even deeper Roland lore up his sleeve. “I had the Roland CR-78 and then a TR-808, but before those,” he adds with a twinkle in his eye, “someone lent me the Bentley Rhythm Ace.” Jones recalls the early experiments which ended up shaping his style. “I had a piano at home and that was the genesis of the one-man band there. Playing along with beats, I thought, ‘I could combine these.’”

I had a piano at home and that was the genesis of the one-man band. Playing along with beats, I thought, ‘I could combine these.'

Those early rehearsals eventually led all the way to the Live Aid stage, where Jones performed his plaintive “Hide and Seek” to nearly two billion viewers. “It’s impossible to not regard it as one of the highlights of my life,” says Jones. “People didn’t know I could play the piano. They thought I was just a synth guy. It wasn’t one of the big hits, but it was a song about hope, so I thought it was right for that day.”

Despite all the musical royalty around, Jones insists it wasn’t so easy to connect with his contemporaries back then. “Everyone was so manically busy. I was working 365 days a year on one thing or another, literally Christmas Day. There was very little time to hang out with anybody.”

The years have rectified this, however. “Recently, I’ve gotten to know the guys in OMD, the Kym Wylde band, and Nik Kershaw. Midge Ure [Ultravox] is a really good friend.”

Transform features a number of collaborations with electronic artist BT, whose synth-pop duo All Hail the Silence is opening Jones current tour, one that also includes Montreal’s Men Without Hats.

Jones explains how the connection evolved. “Robbie said to me, ‘You’ve really got to check BT out.’ So I did and we’d discuss, ‘How did he do this?’ Four years ago, he was doing an orchestral-electronic fusion gig in Miami. I told Robbie we had to fly down. BT gave me a namecheck from the stage, which was completely embarrassing. We met afterward and decided we should work together.”

Bronnimann adds a little-known fact, bringing the conversation full circle. “I think BT said “Hide and Seek” was his favorite song. He used to listen to it riding around on his bicycle.”

“What I’m hoping is this is the first round of curating electronic pop tours,” Jones continues. “Not just ‘80s, but cross-generational.”

Hours later, in front of a packed house at the Moore, the success of Jones’ electro-festival concept is undeniable. All Hail the Silence impress the crowd with an energized set of anthems, buoyed by BT’s festival-honed live presence. Reminding audience members they were more than just “The Safety Dance,” Men Without Hats deliver punk-edged versions of “Pop Goes the World,” “Where Do the Boys Go,” and a handful of new tunes.

By the time the room is singing along in unison to the “Whoa whoa whoa-ohs” of “Things Can Only Get Better,” it’s hard to dispute Jones’ words from earlier in the evening: “When the world has dumped on you, and you feel depressed and negative, music can lift your spirits—just for a brief moment—and get you through the next bit. That’s what I always think of when I’m writing. That particular song is there for a reason.”

Transformative, indeed.

GEAR LIST

CURRENT: SYSTEM-8, RD-2000, V-Mixing System, Roland Cloud

VINTAGE: CR-78, JUPITER-8, JX-3P, TR-808

Header Image by Simon Fowler